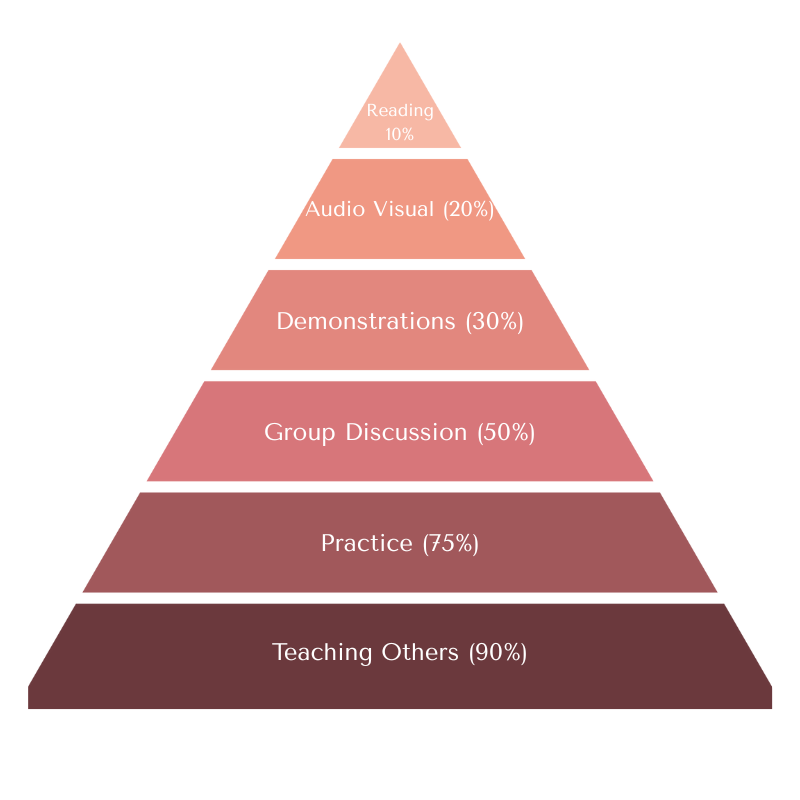

The pyramid of learning: you've probably seen it in a teacher training, shared on LinkedIn by that one colleague who posts motivational quotes, or pinned to the wall of every education conference. It’s a sleek, colorful pyramid claiming you only remember 10% of what you read but a whopping 90% of what you teach others.

It looks official. It cites "research." It has precise percentages that make you think someone spent years in a lab with clipboards and very patient test subjects. And best of all, it confirms what every educator secretly wants — that all those interactive activities and group projects aren't just keeping students busy, they're actually scientifically superior.

There's just one teeny-tiny problem with the pyramid of learning: there’s no actual research to back any of it up.

The Pyramid of Learning has become one of the most widely shared "facts" in education, but it has roughly the same research foundation as horoscopes:

- Specific percentages are made up.

- Original studies don't exist.

- The credible sources are nowhere to be found.

This pyramid refuses to die because it tells educators exactly what they want to hear in language that sounds impressively scientific.

It's educational comfort food: tasty, satisfying, and completely lacking in nutritional value.

Let’s look at the pyramid of learning to see what it gets right (and mostly wrong).

What Is the Pyramid of Learning?

The Pyramid of Learning is a widely circulated educational model that claims to show precise retention rates for different learning methods suggesting people remember: 10% of what they read, 20% of what they hear, and 90% of what they teach others. It appears in countless training materials and presentations, but these percentages have no legitimate research foundation.

Picture a colorful, official-looking pyramid divided into neat sections, each labeled with a learning method and its supposed retention rate. Oh, it’s right here.

Made that myself, mind you — so be kind.

Reading sits sadly at the top with a measly 10%, while "teaching others" proudly crowns the bottom at 90%.

It's educational eye candy that makes complex learning science look beautifully simple.

The pyramid has become the holy grail of active learning advocates, cited everywhere from corporate training to university pedagogy courses. It's so ubiquitous that questioning it feels like educational heresy.

Yet, here’s the truth: those numbers were essentially pulled from thin air, then photocopied and shared until they achieved the status of common knowledge. It's the educational equivalent of urban legends, except with more PowerPoint slides.

The Pyramid of Learning’s Hits and Misses

Let's break down what the Pyramid of Learning claims versus what science says about it.

What the Pyramid Claims (With Complete Confidence):

- 10% retention from reading — apparently books are basically useless

- 20% from hearing lectures — professors everywhere weep

- 30% from demonstrations — getting warmer, but still pretty terrible

- 50% from discussions — now we're talking, apparently

- 75% from practice — almost there!

- 90% from teaching others — the holy grail of learning

These numbers are presented with the kind of precision that makes you think someone measured them with scientific instruments down to the decimal point (or at least nicely rounded).

Why These Numbers Are Educational Fan Fiction:

No research study has ever produced these specific percentages. Not one. Researchers have spent decades trying to trace these numbers back to their source, and the trail always goes cold. It's like trying to find the original person who said "money can't buy happiness" — except in this case, the saying is shaping how millions of people approach education.

The closest anyone can get to a source is a misinterpretation of studies that never actually measured retention rates this way. It's basically a decades-long game of educational telephone where each retelling made the "facts" more specific and authoritative.

What the Pyramid of Learning Gets Right…

Now, the pyramid isn’t completely wrong about everything. As much as I’d like to deal in absolutes, I have to get some credit where credit is due.

- Active learning generally is better than passive learning. Students who engage with material through discussion, practice, and teaching do tend to understand and retain information better than those who just sit and listen. This isn't controversial — it's backed by actual research.

- Variety in teaching methods does help. Using multiple approaches can reinforce learning and accommodate different learning preferences. No argument there.

- Teaching others can deepen your own understanding. When you have to explain something clearly, you often discover gaps in your own knowledge. Teachers and tutors frequently report learning more about their subjects through teaching.

The pyramid gets the general direction right: more engagement typically leads to better learning outcomes.

But here's where it goes off the rails: those precise percentages are pure fiction, and the pyramid oversimplifies learning to an absurd degree. It's like saying "exercise is good for you" and then claiming jogging for exactly 23.7 minutes burns precisely 847 calories for everyone.

It’s just not true (or generally applicable).

And What the Pyramid Gets Dangerously Wrong

Yes, the pyramid gets the general spirit of active learning right, but it commits some serious educational crimes that have real consequences.

- It oversimplifies how learning actually works. Learning isn't a simple input-output machine where method X always produces retention rate Y. Your brain doesn't care about teaching methods as much as it cares about prior knowledge, motivation, sleep quality, and whether you actually understand what you're trying to learn.

- It ignores individual differences completely. Some people genuinely learn better from reading. Others need hands-on practice. The pyramid suggests there's one universal hierarchy that applies to everyone, which is like claiming everyone should wear size 9 shoes because that's the "optimal" size.

- It creates false hierarchies that shame effective teaching. Lectures get labeled as inherently inferior, making professors feel guilty about using direct instruction even when it's the most efficient way to convey information. Sometimes you just need someone to explain photosynthesis clearly, not role-play as a chloroplast.

- It promotes "edutainment" over substance. The pyramid suggests that making something active automatically makes it better, leading to elaborate activities that prioritize engagement over actual learning. Students end up having fun while learning nothing.

It makes educators focus on method over meaning, style over substance.

How to Actually Improve Learning

Instead of chasing pyramid percentages, focus on what education research actually shows works.

- Match methods to content and learners. Some concepts are best explained through direct instruction, others through hands-on practice. Advanced calculus might need lectures and problem-solving, while CPR training obviously requires physical practice. Revolutionary idea: different subjects need different approaches.

- Use variety strategically, not religiously. Don't throw in group work just because the pyramid says it's "better." Use multiple methods when they genuinely serve the learning objectives, not because you're trying to hit some imaginary retention percentage.

- Focus on understanding over activity. A boring lecture that creates genuine understanding beats an entertaining activity that teaches nothing. Your brain doesn't award extra points for fun — it cares about whether information makes sense and connects to what you already know.

- Test actual learning, not engagement. Students can be highly engaged while learning absolutely nothing. Measure whether they can actually apply knowledge, solve problems, or explain concepts, not whether they enjoyed the process.

- Consider prior knowledge and motivation. These matter more than any teaching method. A motivated student with good background knowledge will learn from almost anything. A confused, unmotivated student won't learn much regardless of how "active" the lesson is.

Stop chasing perfect pyramids. Start chasing actual results.

Pretty Pictures vs. Messy Reality

Learning isn't a neat pyramid with precise percentages. It's a chaotic, individual, context-dependent process that refuses to fit into tidy infographics.

The real world of education is messier than any model can capture. Sometimes a brilliant lecture beats a mediocre group activity. Sometimes reading is exactly what someone needs. And sometimes the "inferior" method works perfectly for the right person at the right time.

Stop letting pretty pictures dictate your teaching or learning choices. Trust research over infographics, evidence over eye candy, and results over retail pedagogy.

Your brain deserves better than educational folklore masquerading as science.

Subscribe to Hold That Thought for more myth-busting insights that actually help you learn better.

.png)

.png)